- Home

- Harper, Valerie

B007Z4RWGY EBOK

B007Z4RWGY EBOK Read online

Thank you for purchasing this Gallery Books eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Gallery Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Epilogue

Great Things People Have Said

Acknowledgments

Photographs

Photo Credits

About Valerie Harper

For Tony and Cristina

and Rhoda Rooters Everywhere

PROLOGUE

I first met Rhoda Morgenstern in the spring of 1970 at an old round oak table in the breakfast nook of the small house I was renting in West Hollywood. Through an amazing stroke of luck, CBS had sent me—an unknown actress—an incredible script for the pilot of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Rhoda—free-spirited, funny, and from the Bronx—leaped off the page and grabbed me with her honest and brash humor. This was a woman I liked—no, a woman I loved. This was a woman I wanted to play. And somehow I got the chance.

For nine incredible years I was lucky enough to be Rhoda Morgenstern, who was as funny and as insecure—as downright relatable—as they come. Through Rhoda I met the most supportive, wonderful, and talented television family I could have possibly imagined: Jim Brooks, Allan Burns, Mary Tyler Moore, Ed Asner, Gavin MacLeod, Ted Knight, Cloris Leachman, Betty White, Georgia Engel, Charlotte Brown, Nancy Walker, Harold Gould, Julie Kavner, and many more. To this day, strangers greet me, their faces lit up with happiness and recognition, as if they are meeting an old friend or relative—one they actually like!

In 2007 I was invited, along with Mary and Ed, to be a presenter at the Screen Actors Guild Awards. A week later, I heard that Cloris would be there as well. I suggested to the show’s producers that if they had the four of us, why not invite all seven cast mates, including Gavin, Betty, and Georgia, too. It would be the first time the entire group had reunited in public since 1991.

It was delightful to be with the whole gang again. Backstage was like a company picnic or a family reunion. We schmoozed and dug in to the delicious buffet (always a standout for me at an awards ceremony), and we were quickly lost in our own little world—the same world where we’d all met back in 1970. Nearly forty years later, here were all my friends, the people with whom I loved to work—my very first television family.

Then it was showtime. The announcers called our names, and one by one, we walked single file out on the stage. The applause was thunderous. The star-studded crowd was on their feet: It wasn’t a standing ovation, it was a jumping-up-and-down ovation. And suddenly, I remembered how much the show I loved to work on, the television family I was thrilled to spend every day with, meant not just to me but to our peers in the Shrine Auditorium and, most important, to audiences everywhere.

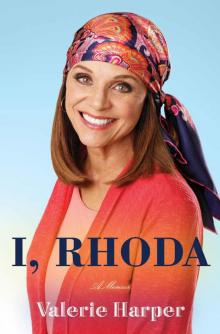

Being and becoming Rhoda Morgenstern has been such a fantastic journey filled with so many hilarious and wonderful people that I wanted to share it with everyone—fans, family, and friends. It has brought such joy into my life, provided so many opportunities, and filled me with so many spectacular memories that I decided to write a book about it. So I did. I, Rhoda is a book about me, about Rhoda, and about the people I love.

chapter

ONE

“Valerie, don’t overdo.” This parental reprimand was the constant refrain of my childhood. One more jump off the diving board when my fingertips were shriveled and my lips blue. One more turn on the swings when my palms were long since shredded by the metal chains as I tried to propel myself higher. One more twirl around the living room to “The Blue Danube,” even though my legs were already covered in rug burns. One more. One more.

I was also always looking for something to eat. When I was two years old, I bit the tail of our neighbors’ yellow Labrador because it looked delicious. I couldn’t help myself—I was drawn to that fluffy golden Twinkie of a tail, and I just had to sink my teeth into it. The dog was not amused; he spun around and bit me right on the lip. (It would be years before I’d overcome my fear of dogs. Though in truth, perhaps they should have feared me . . . )

When I was three years old, while watching my mother get dressed for the evening, I uncorked her beautiful bottle of perfume, Intoxication by d’Orsay. The bottle was so stylish, so alluring. It was in the shape of a cut-glass liquor decanter. How could I resist? I chugged the entire bottle in one gulp. Like the Labrador’s tail, the perfume did not taste as good as it looked and boy, did it burn as it went down! Throughout my life I’ve had no desire to drink anything intoxicating because to me it all tastes like perfume. Talk about aversion therapy!

My mother, Iva Mildred McConnell, was a petite, blue-eyed, blond Canadian. She met my father, the tall, dark, and handsome Howard Donald Harper, through their mutual interest in hockey. Mom played on a women’s team in Canada and spotted Dad at a match where he was playing for a visiting team—the Oakland Sheiks, who were named after Rudolph Valentino’s famed role.

My mother had always dreamed of becoming a doctor, but her parents insisted that she go into teaching instead. She first taught eight grades, all together in a one-room schoolhouse out on the Saskatchewan prairie, where each row in her classroom was a different grade. After about two years, when she’d saved up enough money, she put herself through nursing school and became a registered nurse, a job she truly loved. As much as she enjoyed nursing, when she met Dad, she obeyed the edict of the day: “No wife of mine goes to work.” Throughout most of my childhood, Mom stayed at home with my sister, Leah, my brother, Don, and me, though she always rejected the term housewife. “I’m not married to the house, I’m a home executive,” she would say. How true.

My dad was fabulous and charming—a radiantly positive man with a big smile. When his brief professional hockey career came to an end, he became a lighting salesman. One of several companies he worked for did the lighting for New York City’s Holland Tunnel—a fact we were reminded of every time we drove into the city from New Jersey. He also dealt in those unflattering lights that used to be in every ladies’ room, the fluorescent bulbs that make everyone look like the Cryptkeeper.

Because he was a sales manager and trained new salesmen, my father was often on the road. He also received regular promotions, which meant that my family moved every two or three years as Dad moved up the ladder. Most summers we traveled with my father to work, incorporating family visits to my mom’s folks in Vancouver. We had the best times with my Canadian cousins, Michael and Dean—swimming, walking trails, exploring the enormous Stanley Park. Some years we’d go see my dad’s relatives in California, where Don and I learned to ride two-wheelers in Canoga Park. Or we packed our things to move to another town and settle in before the school year began. We spent a lot of hours crammed into the back of our Kaiser-Frazer car, traversing the West Coast. During these trips, my little brother, Don, became obsessed with cars and developed the charming habit of naming each and every make and model approaching from the opposite direction, which didn’t make the time pass any faster. Leah, a perpetual joker, continually pointed out deer along the side of the road, but when I looked, they were always gone—if they were even there in the first place. Three kid

s in an unair-conditioned vehicle in the height of a California summer must have been a real picnic for my parents.

I was born weeks earlier than expected in Suffern, New York. My parents were on a business trip when my mother went into labor. My father had gone to a tennis match, so my mother lumbered out of the hotel, into a cab, and to the nearest hospital—the Good Samaritan, a fitting name under the circumstances. My mother was so sure she was having a boy, the only name they’d picked was Charles Howard. When my father arrived and learned I was a girl, he was still carrying the program from the tennis tournament. The women’s doubles champions were Valerie Scott and Kay Stammers. So Valerie Kathryn Harper was born—and she would never be very good at playing tennis, despite her namesakes.

I came into the world at four in the morning on August 22, 1939, weighing in at a hefty eight pounds, fourteen ounces. I was the middle child—an average, chunky little brunette with a pronounced lisp that I didn’t lose until the third grade. My older sister, Leah, was a tall, slender, pretty blonde. When discussing my figure, my mother used to lower her voice, as if imparting a disgraceful secret, and say, “Valerie, you’re short-waisted.” It seemed that I was cursed indeed to have a waist that was short. At the time, I wasn’t at all sure what that meant, but I accepted it because Mom said I’d gotten it from her. How bad could it be? I also harbored the hope that, as I grew, my waist would get longer and my pronunciation of S’s would improve.

Despite the difference in our physiques, my mother liked to dress Leah and me in matching outfits. Leah was able to get her clothes in the regular children’s department, whereas my outfits came from the “Chubby” section. Chubby! What a word. It lacked the subterfuge of the boys’ equivalent, “Husky.” Chubby meant fat or, at any rate, not slim. There was no denying it. I used to cringe when my mother would hold up a dress she thought would look cute on Leah and ask the sales clerk if they stocked the same dress in “chubby” for me.

My younger brother, Don, was born two and a half years after I was, when we were living in Northampton, Massachusetts. My first memory of my brother is of him peeing on my hair as my mother changed his diaper. “Take him back to the hospital,” I told my mother. “He pee-peed on my curls.” Despite my protests, Don was there to stay. At least he provided Leah and me with a soft (often damp) baby to dress up like a doll and take turns holding.

A few years after my brother’s birth, my father was reassigned to the tristate area. We moved from Northampton to South Orange, New Jersey, and our nomadic lifestyle was put on hold. We settled into a house with a huge backyard where Don, Leah, and I frequently played war games, pretending we were the Allies and the Japanese. Leah usually forced me to be a wounded Japanese soldier, which meant I had to lie on the ground while Don and Leah used me as a shield. It wasn’t the most exciting role available in our make-believe battlefield. Luckily, when I enrolled in kindergarten at the Mountain View School, I was first introduced to the stage.

I got my first big break playing a snowflake in a school recital. My mother made me a fluffy white costume, and along with the rest of the girls in my class, I tiptoed onto the stage, fluttered around a bit, and then, to portray accumulation, fell as silently as possible to the floor and froze. I guess all my war games with Leah and Don came in handy after all. The next year, I was given the role of a dove in the manger scene of the Christmas pageant. It was my first speaking role. My mother made me a gray costume with wings and a hood with a protruding beak. Leah, a realist and a fashionista, noted, “You look like a pigeon. Aren’t doves white?”

“Doves can be gray or white,” Mom explained.

I accepted my mom’s explanation, although it did seem that a white dove might have been more elegant. At the pageant, after I said my line, “I am the dove who cooed Him to sleep,” I cooed a little too loudly and got a laugh—my first laugh! Only, instead of seeing it as a good thing, I was worried that I’d done something wrong and decided to stick with dance to save myself from further embarrassment. And since music was such an important part of our household, dancing seemed only natural to me.

My parents were always trying to open our minds and inspire us to express ourselves. They diligently encouraged us to try new things and be open to a wide variety of experiences. At bath time my mother would switch on the radio, often something dynamic like a Sousa march, and give us what she called “air baths,” where we would run, skip, and dance around the house naked until we got in the tub.

Both my parents loved music and turned us on to all kinds of songs. My mother was a self-taught pianist. She played everything—ragtime, honky-tonk, pop standards—everything but classical music, which she appreciated but said made her sad. Some of my fondest childhood memories are of singing around the piano with my parents, sister, and brother, or listening to my father’s smooth baritone as he belted out “Stardust,” “Deep Purple,” and other hits from the 1940s.

It was during this period in South Orange that my parents took me to the ballet for the first time. I was enthralled by the opening ballet—Interplay, choreographed by Jerome Robbins and starring Michael Kidd and Ruth Ann Koesun as a stagehand and a ballerina. Except for a ladder and a work light, the stage was hauntingly empty. The ballerina, in her pink tights and rehearsal leotard, and the stagehand, in his overalls, danced a beautiful pas de deux. I was entranced and inspired. On the way home from the theater, I told my parents that I was going to be a dancer.

This probably didn’t come as a surprise to them. Even at six years old, I knew I wanted to be a performer. I just wasn’t sure what my outlet would be—dance, ice-skating, roller-skating, gymnastics. I even considered becoming an aerialist. After my parents took me to the circus, I tried to re-create one of the acrobats’ feats by racing my tricycle across our cement basement floor, then standing up on the handlebars. It was harder than it looked; I wound up cross-eyed with a concussion.

To their credit, my parents took my declaration that I was going to be a dancer quite seriously. (They were probably relieved that I’d given up on the circus.) Although we were middle-class, Dad always found the money for my lessons at whichever local dance school Mom had discovered.

When first grade finished, Dad was dispatched to the West Coast, moving us to Altadena, then to Pasadena, California, where I instantly embraced my surroundings; the towering palm trees were like nothing grown in New Jersey. We lived on Orange Grove Boulevard, which meant the Rose Bowl Parade went right by our house. Every year Dad made money hand over fist by charging parade-goers to park their cars in our backyard.

Because we moved around a lot, we three kids were adept at making friends quickly, and we even managed to keep in touch with people we’d left behind. To an outgoing and energetic seven-year-old like me, moving to a new city and starting a new school was more exciting than scary. In Altadena, Mom enrolled us at Thomas Edison Grammar, where I made friends quickly and settled into our new West Coast environs with ease.

In Pasadena, I became serious about ballet. My teacher was Pamela Andre, a calm, soft-spoken former professional dancer. She had a studio downtown where I took lessons twice a week. This was the big time. Before, Mom had found me whatever local dance school was convenient, and there I bounced around with my classmates pretending to be butterflies, not exactly preparing for the Bolshoi.

Whenever we moved during the school year, my mother had to find public schools that would take us midterm. When we relocated to Pasadena, the only place that had room for me was St. Andrews, a Catholic school. Before coming out west, we had attended Sunday school at the nearest Protestant church. But once my mother saw how rigorous my education was compared to that of Leah, who was still in public school, she decided that all three of us would attend Catholic school whenever possible.

When the next school year rolled around, my mother put us into a Catholic boarding school in Pomona so that our educations would not be affected by my father’s travel schedule. This allowed her to accompany Dad on his longer road trips. The Acade

my of the Holy Names was a beautiful Mission-style school located next to an orange grove. It was an idyllic setting, apart from the fact that they used to burn smudge pots in the fields to prevent frost from ruining the orange crop over the winter. When we woke up in the morning, we had little black Charlie Chaplin mustaches on our upper lips from breathing in the smoke. Clearly, this was before there was an EPA.

We spent only one year at the Academy of the Holy Names before moving to Monroe, Michigan, where Leah and I were enrolled in St. Mary’s Academy, another boarding school. (Don attended the boys’ school, Hall of the Divine Child.) I was ten years old when we moved to Michigan, old enough to sense that there was tension between my parents—arguments, sharp words. There was a girl in my class whose parents were divorced, something that was still scandalous back in the 1940s. I had a suspicion that this was where my folks were headed, and I wanted to prevent it. So, one Sunday when my parents were visiting us, I tried out my powers of manipulation on them. “Poor Marlene,” I said, “her mom and dad are divorced. I’m so glad that’s not you two.” (I could be a devious, self-preserving little devil sometimes.) I saw my parents exchange a knowing glance. I felt I had guilted them into staying together, at least for the time being. Mission accomplished.

I loved the year I spent at beautiful, pastoral St. Mary’s. We ice-skated on a lake and picked apples from an orchard on campus. My teachers, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, were fabulous—strict but devoted to their students. I made a wonderful friend, Bonnie MacKinaw, a tall girl with a terrific laugh, and from my classmates, I learned all sorts of skills, including embroidery and card games. Mom was shocked that I came home from Catholic school a gambler! I was also jacks champion of the fifth grade. Although I wasn’t surprised when my parents told me that we were moving again, I was sad to leave this remarkable place and Bonnie.

B007Z4RWGY EBOK

B007Z4RWGY EBOK