- Home

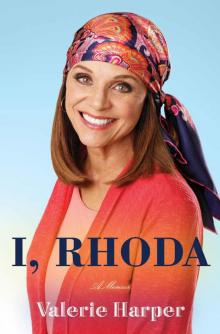

- Harper, Valerie

B007Z4RWGY EBOK Page 4

B007Z4RWGY EBOK Read online

Page 4

Since neither of us could drive, Beth and I caught the bus on Melrose Avenue to the fabled Paramount studios. Working on the movie was a totally new experience. While I was accustomed to the backstage camaraderie on Broadway, the soundstages in Los Angeles were incredibly exciting—small bustling cities filled with famous faces. The first time I saw Marlon Brando in L.A.— he was filming One-Eyed Jacks on the lot—I started screaming like a crazed groupie. Hope Holiday, an adorable platinum blonde who was a singer on Abner, took me by the arm and told me never to embarrass her like that again. “Don’t act like a silly fan. You’re a professional on a movie,” she explained. “Act like one.” She’s lucky I didn’t yell out, “Hey, Marlon, I studied ballet in Carnegie Hall when you lived there.”

Although we had early calls on weekdays, we had the weekends off. In our spare time Beth and I would ride the bus down to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, putting our feet in the stars’ footprints. We went out to Anaheim to visit a new amusement park that had just opened called Disneyland. And because we were constantly dieting, we’d eat steaks at Diamond Jim’s on Hollywood Boulevard. In those days steak was a diet food; at least when served without potatoes and fried onion rings.

When the Abner shoot wrapped, I suddenly had time on my hands and didn’t know what was going to come next. Work had started to find me, so I developed the ability to live with uncertainty—a great asset to anyone in show business. I knew there would be periods without a paycheck. But in order to survive in the business, I’d have to learn to live with that reality.

When I returned to New York, Iva and I decided to rent an apartment together. From the earliest days of our friendship I’ve called her “Iva the Oracle” because she always gives the wisest advice no matter the subject: You need something, she knows where to get it, or at the very least will find out how to get it for you. She bought newspapers right away and began circling apartment listings all over the happening Greenwich Village, but we eventually settled on a studio apartment on West Fifty-fifth Street. We figured it would be good to be in the heart of the city, close to the Broadway theaters where we worked. We often ate at Jim Downey’s Steak House, a fantastic show business restaurant and hangout on Forty-fourth Street and Eighth Avenue, where we felt very much a part of the Broadway community. Everybody from chorus members to major theater actors to stars such as Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman, both of whom Iva and I saw several times, frequented Downey’s.

I was moping around wondering what would come next in my life when I received a phone call from Onna White, a choreographer who was working on a new production called Take Me Along, a musical based on Eugene O’Neill’s play Ah, Wilderness. It was being produced by the extremely successful David Merrick, who went on to produce 42nd Street and Oliver!, as well as other huge Broadway hits. Jackie Gleason was going to star.

At Michael Kidd’s kind suggestion, Onna was asking me to audition for the show. I was very flattered. She needed strong female dancers for a particularly strenuous Beardsley dream ballet. The first day of rehearsal was a spectacular event. We assembled in a large studio and were introduced to the cast and crew. We listened to the leads read through the script and then divided up—principals, singers, dancers—into different studios to work on our part of the show. When I look back, I realize our studio was a shabby, airless space with less than immaculate floors. The walls were covered in fuzzy pink fiberglass insulation that looked like cotton candy. Looks aside, our studio embodied the hardworking romance of theater, and I was madly in love with all of it.

The show involved all sorts of unusual choreography. In one number with Jackie Gleason, I was a dance hall girl. I wore a black corset with a short flounce, bright orange tights, black patent boots that laced up to midcalf, and a turn-of-the-century wig. (Oh, how we begged the costume designer to get rid of those orange tights, which made our legs look like fluorescent sausages!) The pièce de résistance was a huge pair of dice made out of felt, strategically placed, one over each breast. In my “Dice Girl” costume, I felt like a grotesque Lillian Russell. Along with two other dancers, I jiggled my dice and sang in a squeaky chorine voice, “You can shake ’em if you promise not to break ’em. After all, they’re the only pair I’ve got.” It was bawdy and silly and fun to perform.

Jackie Gleason was at the height of his fame when Take Me Along opened. His nickname among other comics was “The Great One.” It was apt. He was hysterically funny. He had huge hangdog eyes and called everyone “Kid” in a manner that was endearing rather than demeaning.

I’d heard rumors about Jackie’s fondness for alcohol. There were certainly nights when he may have had one too many. On those occasions, the pace of the show slowed down a bit, although I’m sure the audience didn’t notice. Jackie always seemed to pull it off.

Our opening-night party was held at Sardi’s on Forty-fourth Street, opposite Shubert Alley. An area had been roped off for the stars—Jackie, Walter Pidgeon, Una Merkel—as well as the director and producers. The minute Jackie saw the velvet rope dividing the bigwigs from the rest of the company, he got his working-class Irish up. He was outraged and demanded that the rope be taken away. When no one came forward, he moved the rope himself. “There’s going to be no steerage class at this party,” he said. We were all one company celebrating a successful opening, and he made sure everyone was included equally in the festivities.

There was a terrifying moment during a matinee in the middle of a huge production number. A deranged young man stood up on the railing of his opera box right above the stage, poised to jump. It was John Wilkes Booth time. Jackie signaled the orchestra to stop with one hand, then held the other hand up high like a traffic cop. “Hold it right there, pal.” (Yes, he actually said “pal.”) He engaged the man long enough for security to pull him back into the box. To a very nervous audience, he announced, “Sorry, folks, everybody wants to get into the act.” I love Jackie Gleason for many reasons, and this is one of them.

During Take Me Along, I got my first taste of the union organizing that went on behind the scenes in the theater. A few months into our run, Actors’ Equity called a strike. They were demanding higher minimum pay and better working conditions for performers—no concrete floors in rehearsal studios, no rooms filled with asbestos.

Although we were locked out, we had to come to the theater every day to prove we were showing up for work. One afternoon while we were waiting in Shubert Alley, our boss, David Merrick, appeared dressed in his “prince of darkness” black suit with his manicured black mustache. As he passed by, he said, “You’ll never work for me again.”

My friend Gene Varrone, a wonderful tenor singer, called out, “Until you need us, David. Until you need us.” As it turned out, Gene was right.

During the strike, most of us attended union rallies at the Edison Hotel ballroom; many stars supported the effort as well. Shelley Winters and Celeste Holm attended one particularly acrimonious meeting. I’d seen many of their films with my mother on “dish night” at Varsity Theatre in Ashland. (Back then, they incentivized people to go to the movies by giving out free dishes to patrons once a week. And I’ll never forget Celeste’s performance in All About Eve and Shelley’s turn in A Place in the Sun.) Celeste was an elegant blonde, a beautiful, well-spoken woman. I watched as she stood up and said, “Everyone! We must calm down. We are not a union, we are a guild!” She wanted us to think of ourselves as artists, not activists.

Then Shelley Winters stood up and shouted in her brassy voice, “Celeste, sit down! You don’t know your ass from your elbow. These kids are dancing for eight hours at a time on concrete and destroying their legs.” It was an extraordinary moment. Here I was just starting out, and these legendary stars, women I’d seen only on the screen, were fighting for my professional well-being. It was so moving to actually be part of this engaged show business community.

After the strike, Take Me Along settled into a yearlong run, and Jackie won a Tony for his role as Sid Davis. One evening when the show

let out, Jim Cresson, one of the principal actors, asked me if I’d ever considered studying to become an actor. He’d heard me fooling around backstage, doing imitations of movie stars, and thought I should consider taking classes. I told him about my experience at Cassavetes’s class and how I’d felt like a complete fish out of water. Jim suggested that I go to his acting teacher, Mary Tarcai. Since I had migrated away from classical ballet and into the belly of show business, I figured I might as well explore other paths and signed up.

Mary was an intense, powerful, and extremely direct teacher who always wore black. “I’m in mourning for my career,” she explained when anyone questioned her dress code. She’d been caught up in the Communist witch hunt in Hollywood in the 1950s and was blacklisted when she refused to name names.

By coincidence, her classes met in the same studio where my old school Quintano’s had been. At least superficially, I felt at home. At first I was terrified to participate in scenes. I wasn’t sure of what I was doing. Mary was a rigorous teacher—demanding but supportive and very committed to her students. I often failed miserably in class. “Good,” she’d say. “Fail here in the studio, not out there when you’re working on a role.” Slowly, I began to grasp how to build a character and how to remain true to a playwright’s vision. “Acting is not about you self-expressing,” Mary said. “It’s about you creating other people.”

Iva, who was still dancing in the long-running My Fair Lady, and I moved from our studio on West Fifty-fifth Street to her aunt Ada’s beautiful town house on Embassy Row, on Sixty-seventh between Fifth and Madison. (I can only imagine how thrilled Aunt Ada must have been to have two young dancers under her roof.) Eventually, I moved in with my close friend from Take Me Along, Arlene Golonka.

Arlene lived in a seven-room apartment on West 101st Street and Riverside Drive—five girls in all, some of whom were in the business. The atmosphere in the apartment was just this side of riotous. One of our roommates was a very attractive German brunette named Eva, who never missed an opportunity to wander into the living room in her black lace underwear when another girl had a date over, saying, “Ach, I deedn’t know zair vas anyvon heah!”

Arlene was an adorable Polish-American blonde from Chicago. She was wildly funny, very talented, and full of energy. She played Belle, the prostitute in Take Me Along, and as a principal actor, she had her own dressing room. Lonely and wanting to be with her pals—a lovely redheaded dancer, Nicole Barth, and me—Arlene moved kit and kaboodle into the large chorus dressing room in the basement.

One afternoon while we were previewing the show in Philadelphia, the three of us were having a snack in a coffee shop when Mel Brooks, who was previewing his own show, approached us. “There they are: chocolate, strawberry, and vanilla,” he said. Whenever any of us ran into Mel in the years to come, he made the same joke about our hair color.

Iva, Nicole, and I were chorus dancers. There is something truly wonderful about dancing in a chorus, with everyone moving through space as individuals who together make up a whole dance. It’s a specific experience that an individual performer can never achieve alone. Arlene was an actor and, like Jim Cresson, she urged me to pursue acting. She would call me from her auditions and beg me to show up. “Val, I’m at the Martin Beck Theatre. I’m auditioning for Abe Burrows. Get down here now,” she would whisper from backstage. When I protested that I didn’t have an agent, Arlene wouldn’t listen. “Just come to the door and tell them you’re here to read. If I don’t get the part, maybe you will.” The extent of Arlene’s generosity and enthusiasm for her friends’ success was a rarity in the business.

With Arlene’s coaching, Mary Tarcai’s cold-reading class, and auditions one on top of the other, I felt myself improving, but I hadn’t caught a break. Luckily, I had a new source of income—industrial shows, or trade shows. These productions were a big deal back then. These presentations introduced new or featured products to the corporate sales forces before they hit the market with a customized musical stage show. They paid well and became a lifesaver for me. (So was unemployment insurance and, on occasion, Mom and Dad’s help when I was between jobs.) For several years I did the Milliken Breakfast Show during fashion week. It was a splashy, beautifully produced musical show put on for the apparel buyers in the posh digs of the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria or the Astor Hotel at eight A.M.

The Milliken show, which ran for two weeks, was the ultimate in corporate theater—a first-rate song-and-dance comedy revue that parodied other musicals with special lyrics praising Milliken fabric. Thousands of textile-industry executives and buyers attended these performances, had breakfast, and were in the market buying by nine A.M. Milliken hired only Broadway singers and dancers to model the fashions and always booked marquee stars, like Joel Grey, Nancy Walker, Bert Lahr, Phil Silvers, and later on, David Cassidy.

Although I’d been hoping to move from dancing into acting, I needed a job, so in 1961 I auditioned for the chorus of Michael Kidd’s new Broadway show, Wildcat, a musical starring Lucille Ball. I’d grown up loving her feature films and her landmark TV show, so seeing Lucy in person was stunning. With her dazzling aquamarine eyes, fiery hair, and luminescent skin, Lucy seemed to radiate light from within. She was wonderful, warm, and friendly to the entire cast.

The first time the cast convened to read through the script, Lucy insisted that everyone introduce him- or herself. I was sitting next to a beautiful, petite brunette named Penny Ann who had worn hip-hugger pants to the audition. When Penny Ann said her name, Lucy looked up from her script and said, “What’s a Penny Ann?” Then she looked directly at Penny and said, “Look at those saucer eyes, that’s a Penny Ann.”

Lucy looked after all of us. The first time she visited us in our chorus dressing room, she was shocked by how grim it was. She came from Hollywood, the land of clean, well-lit dressing rooms, so she was unaccustomed to the lack of glamour backstage in the old Broadway theaters. When she saw the rough, dirty cinder-block walls, she exclaimed, “I don’t want you living like this. We’ve got to paint the room.”

A few days later, she returned. “Kids, the union says that we can’t paint the dressing room. So how about we all sneak in on the weekend and do it behind their backs.” When the management got wind of what Lucy was up to, they immediately saw to it that the dressing room was painted. It was clear that she used her stardom to help us. When I gave Penny Ann a shower for her upcoming wedding to a tall, blue-eyed Israeli named Zvi Almog, Lucy sent a blender. A real state-of-the-art blender was a big deal in those days. I was on Long Island at Penny’s wedding when Angela gave birth to Virginia Allyson Harper—Ginger—in New Jersey. That was a full day!

Although the show got lukewarm reviews, people flocked to the theater expecting to see Lucy Ricardo, the wacky housewife from I Love Lucy. When the curtain went up, though, they embraced the tough oil prospector Lucy played in Wildcat. With her mile-long legs and huge personality, Lucy filled the theater and enthralled the audience.

One night she truly outdid herself. There was a scene that involved Lucy; her sister Janie, played by Paula Stewart; a ritzy countess, played by Edith King; and a little Yorkshire terrier. The dog was unbelievably well trained, and every performance, he dutifully followed behind Edith, Lucy, and Paula as they crossed the stage. One evening as the Yorkie was making his cross, he suddenly stopped center stage, assumed the position, and pooped. The audience went wild. Edith froze. Lucy dashed offstage and urgently asked the stage manager to hand over a broom and upright dustpan. She returned to the stage and swept up the offending little pile and then turned to the audience. “Next time I’ll read the fine print in my contract.” The audience exploded with laughter and applause. After the show, Lucy later confided to the cast that she was glad it had been a Yorkshire terrier and not a Great Dane.

Wildcat had its share of problems. Lucy suffered bouts of exhaustion and got injured during a performance when part of the oil rig hit her on the head. She was forced to take several leav

es of absence during which the show was dark. But when she recovered, she soldiered on immediately. If not for Lucy’s immense draw, I think we would have closed earlier than we did.

It was during my run in Wildcat that I had my first serious love affair. I had been introduced to a dashing man named Sam by Diana Hunter, a pal, and one of the other Dice Girls from Take Me Along. He was a handsome Princeton boy who worked as a producer on a long-running children’s television show.

A product of the 1950s and Catholic school, I was saving myself for marriage, so I’d rarely let a guy pay my way on a date; I didn’t want to owe anything in return. My catchphrase was “I like you as a friend.” Original, huh? I must have uttered this line hundreds of times.

With Sam it was different. A consummate gentleman, he wouldn’t dream of letting me pay—and, knowing that I was in love with him, I let him. As my pal Gene Varrone would say, “It was a lovely romance.”

Though we were going together, marriage was not a topic of discussion, although I’m sure the question of whether Sam was “the one” was bobbing around in my twenty-two-year-old brain. If it hadn’t been before, Angela’s aunts, Edith and Carmela, made sure it was when they yelled across the lasagna and roast chicken at a family gathering in New Jersey, “So, Sam, when you gonna marry Valerie?”

I was mortified beyond belief. My sensitive dad maneuvered me into a quiet corner and talked me off the emotional ledge. “Don’t be angry at them, Val. They think they’re helping you get married and get pregnant. In that order!”

B007Z4RWGY EBOK

B007Z4RWGY EBOK