- Home

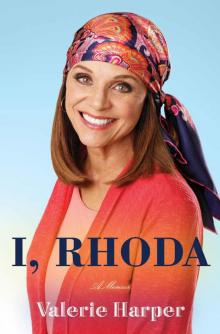

- Harper, Valerie

B007Z4RWGY EBOK Page 7

B007Z4RWGY EBOK Read online

Page 7

As months passed and no work came my way, I started to worry that there was nothing for me to do in California. I missed the theater life I’d left behind on the East Coast. I was nearly thirty years old, which even back then was a little long in the tooth for an actress. Perhaps my ship had sailed.

Fortunately, a call came from Paul Sills, the genius creator of Second City. Every few years, Sills would create a dazzling new theater form. He maintained that theater should deliver powerful, authentic experiences, as well as huge laughs, thrills, and chills. His upcoming endeavor was no exception. He told us that he was developing a production called Story Theatre, and he wanted Dick and me to be in the company.

Story Theatre was a direct evolution of Sills’s work in Second City. Using his mother Viola Spolin’s Theater Games to develop material, he planned to create an evening of comedy, narrative, and movement to tell (or retell) classic folktales and myths. With a company of eight players, he wanted to explore the humor, mystery, and passion at the heart of fairy tales, and examine how the stories we pass down from generation to generation express the human condition. The players would be Dick Schaal, Dick Libertini, Paul Sand, Hamilton Camp, Peter Bonerz, Melinda Dillon, Mary Frann, and Valerie Harper. I was so happy to be invited into this thrilling theatrical process.

Story Theatre was comprised of eight fairy tales or fables such as “Henny Penny,” “The Golden Goose,” and “The Robber Bridegroom,” presented on an empty stage through narration, dialogue, and the use of imaginary objects. Paul planned to have a quartet, The True Brethren led by Hamilton Camp, accompany the performance with songs by Country Joe and the Fish, Bob Dylan, and George Harrison. He decided to develop the show in Los Angeles with an eye to bringing it to Broadway. I was very excited about the prospect of appearing on Broadway once more, this time as an actress instead of a dancer.

Between agreeing to do Story Theatre and beginning rehearsal, Dick and I got involved in another production, one with a very interesting man named C. Robert Holloway, who was something of a jack-of-all-trades—a director, set designer, writer, producer, and eventually good friend. He was writing a play with Richard Levine called The American Nightmare. The show was a send-up of a staged reading put on by the fictitious and quite dreadful British theatrical company called the Royal Chichester Players.

The play was written in a purposefully over-the-top style riddled with purple prose and sly humor. I played two roles—Hitler’s girlfriend Eva Braun at eighteen and Vida Fontanne, a fading stage star who sounded like Tallulah Bankhead. The American Nightmare played only a couple of weekends in a tiny black-box theater on Vermont Avenue, but it was a terrifically funny production that I loved being a part of.

Shortly after it closed, I received a call from C. Robert. He told me that Ethel Winant, head of casting from CBS, had seen the play and wanted to talk to me. Since I didn’t have an agent, she’d had a tough time tracking me down. Ethel was casting The Mary Tyler Moore Show at the time and wanted me to come in and read for Mary’s friend Rhoda.

At first I thought C. Robert was joking. I couldn’t believe I was being asked to audition with a star like Mary Tyler Moore. When he assured me that he wasn’t joking, I asked if he would act as my agent. C. Robert agreed but warned me that he was leaving town and might not be available down the road. I told him that was fine because I didn’t think I had a snowball’s chance in hell of getting the part.

While I didn’t look anything like Mary Tyler Moore, I thought I might not provide enough of a physical contrast to be her sidekick. We were of similar height and both had dark brown hair and small noses. I assumed CBS was looking for a tall, skinny redhead or a short, obese blonde. But as an actor, you audition. You show up, do your best, and hope that if you’re wrong for the part, the casting director might remember you for something else.

CBS sent me the script, and I loved Rhoda immediately; I knew I could play the character. When I saw that she was a Jewish New Yorker, I called up my New York pals to hear their accents and refresh my memory. Penny Ann Green and Gene Varrone, who were both from Brooklyn, helped me figure out how Rhoda spoke. It was also Angela’s voice that I heard in my head when I began to prepare for the role—the cheery, wisecracking old-school New Yorker.

Dick began coaching me. We decided that it would be best if I memorized the audition scenes, something you would never do when auditioning for a play. But I wanted to be able to use props and bring a level of physicality that I thought would be impeded by carrying a script. I also wanted to give the impression that I was a quick study, which I’m not.

Dick and I had a little sailboat in Marina del Rey. The weekend before my audition, we holed up on the boat and began to rehearse. I’m sure all of the folks in the neighboring slips thought we were insane as we repeated the same conversation over and over and over.

The material I was given to prepare was the very first scene of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, in which Rhoda is outside on the balcony, washing windows in the cold. With Dick’s help, I figured out how to pantomime the window and the bucket and communicate the sensation of stepping out of the cold and into Mary’s apartment.

The first person I met on The Mary Tyler Moore Show was a cute-looking, natural redheaded secretary, Pat Nardo. She had a Bronx accent and a welcoming demeanor that calmed this “bundle-of-nerves” actor. Pat went on to become a very funny writer on both Mary Tyler Moore and Rhoda. I entered that place of hope, dread, and possibility . . . the audition room.

Jay Sandrich, the show’s director, and the creators James L. Brooks (whom everyone called Jim) and Allan Burns were there, as well as writer-producer David Davis, who was always known as Dave. It was one of the best audition atmospheres I’ve ever walked into—a roomful of smiling, friendly people. It’s so nice when you don’t have to try to act through your own nerves, plus a veil of negativity from those casting, as is so often the case. Everyone seemed surprised and delighted by the Second City elements I brought to the audition, even laughing aloud when I conjured the cold air with my hands and shut an invisible window. When I was finished, they thanked me for coming in and sent me on my way. Although I felt I’d done well, I had no idea whether I’d be considered for the job.

The next day the network called and said they wanted to see me again, this time to read with Mary. A callback! I couldn’t believe it. I was nervous and excited. I’d made it to the next level, and I was going to meet the marvelous Mary Tyler Moore. I harbored zero hope of getting the part. But since I always treated every audition as an opportunity to improve my acting and conquer my nerves, I figured that reading with someone as accomplished as Mary Tyler Moore would be a great learning experience.

Mary had just come from a ballet lesson (like me, she first trained as a dancer). She wore a pale rose Helanca turtleneck over white trousers. After I gushed about how wonderful she was on The Dick Van Dyke Show, I took a step back and looked her over. She was as thin as a reed. “Look at you in white pants without a long jacket to cover your behind,” I said. (Hell would have to freeze over before I would go out with my top tucked in and my butt in white.) The guys in the room burst out laughing. I had already become Rhoda the Self-Deprecating.

Mary was sweet and warm and immediately put me at ease. We read another scene from the pilot. It went quickly, and again I had no idea how I did. When we were finished, Mary and I chatted a little so that Allan, Jim, Dave, and Jay could see us interacting, and then I drove home.

When I pulled into the driveway ten minutes later, Dick was standing on the front lawn, waving his arms. “You got it! You got it!” he shouted. He looked a little deranged.

“Get in the house,” I replied. “I didn’t get anything.” Back in New York, I had sweated through six callbacks for radio commercials before being turned down. I had become inured to rejection. “I haven’t done a screen test yet,” I continued. “This is Hollywood. No one gets cast without a screen test. Plus, I don’t even look right for the part.” It seemed inconceivable tha

t something so big might work out so easily. This sort of opportunity was the whole reason Dick and I had come to Los Angeles. I couldn’t believe it was happening.

“No,” Dick said. “You got it. Seriously. They want to know who your agent is.”

C. Robert kindly made calls on my behalf but was determined to leave agenting and move to Hawaii. I started out at seven hundred dollars a week to play Rhoda Morgenstern: I was over the moon.

When Dick and I moved to Los Angeles, my only ambition was to work steadily—to get into a play with a decent and successful run, something that didn’t close before it opened. Sure, I’d entertained the notion of working in television, but certainly not as a series regular alongside someone as beloved and respected as Mary Tyler Moore! All my ships seemed to be coming in.

After I was cast, Ethel Winant asked me to come into the CBS offices to meet some of the executives. One of the suits was sitting in a chair with his leg slung over the armrest. He looked me over when I came into the room. “Tell me, Valerie,” he said, “I understand you’re part Spanish.”

“Well, I’m supposed to be, on my dad’s side. You’d have to do a genealogy search to be sure.”

The executive turned to Ethel. “Can we fill our minority quotient with her?”

“I don’t think so,” Ethel said.

“I once did a Mexican hat dance in grammar school. And I wore black braids and a Mexican costume on Broadway in Wildcat,” I offered. “But I don’t think you can pass me off as Latina.”

When I was cast in The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Story Theatre was getting ready to open at the Mark Taper Forum. I was so invested in Paul Sills’s piece that I hoped and prayed I could work out a way to stay in the play while also appearing in the television show. Paul and Gordon Davidson, the director of the Taper, were both delighted that I had landed a series and graciously arranged for another player, the beautiful Mary Frann, to go on for me on Friday nights, the night when The Mary Tyler Moore Show filmed. On all the other nights, I would be able to rush from rehearsals at the studio in time for the curtain at the Mark Taper.

I was thrilled beyond belief for my first day of work on The Mary Tyler Moore Show. I was also terrified that I would bomb. I had the first-day-of-school jitters driving onto that lot—it felt like something straight out of the movies! I pulled in through the CBS gates and into the parking lot that morning, ready to begin my television career, and there it was: my name on my own parking space. This was huge.

I was one of the first people to arrive on the enormous soundstage. Naturally, I gravitated toward the craft services table loaded with coffee, tea, and mountains of pastries. The first person I met was Gavin MacLeod, who was also perusing the donuts. We introduced ourselves. “Don’t these look delicious,” Gavin said, holding up a donut. He spoke my language. We were instant friends for life.

Jay Sandrich, who directed most of the seven seasons of Mary Tyler Moore, took us on a tour of the set, which reminded me of an airplane hangar. Mary’s apartment was in the middle. WJM-TV, the television station, was on the far right; a swing set, which was often turned into Rhoda’s apartment, a restaurant, or whichever set was needed for a particular show, was in the area on the left.

Mary was incredibly sweet as she introduced me around. She never drew attention to the fact that I was clearly the greenest person present. In fact, she went out of her way to explain that I was a stage actor. “Valerie’s from the theater,” she bragged about me as we moved through the soundstage. “She’s a Broadway girl, and she’s doing a play at the Mark Taper at the moment.”

After the tour, we convened around a conference table and began to read through the script. The producers had assembled a unique and talented group of serious actors: Ed Asner was known for playing tough guys. Ted Knight had played Nazis. Gavin MacLeod had played heavies. And Cloris Leachman had been the mom on Lassie. During casting weeks, Dave Davis had glanced out of his second-story office window and noticed an actor with the script preparing to audition. Dave thought to himself, Boy that guy looks like the character Lou Grant. Turned out it was Ed Asner. Actually, this entire group of actors all had impressive résumés and extensive on-screen experience. I was the newbie. The essential common denominator was that we could all play comedy.

Allan, Jim, Jay, Mary, and her husband, Grant Tinker, who was the head of Mary’s production company, set a lighthearted yet professional tone on our first day. I got the impression that we were going to have lots of fun, but we’d lay down some serious comedy, which meant working hard.

Everyone laughed frequently as we read through the pilot. I thought the script was terrific. A show that focused on a woman’s career, not her family or love life, was a new concept. The Mary Tyler Moore Show reflected the way more and more real women were living in the 1970s. It was refreshing and invigorating and addressed the changing attitude toward women in the workplace that had been rippling across the country.

The first read-through felt celebratory, like a little party. I was relieved that after they heard me read Rhoda, I wasn’t fired—I took it as a sign that they meant to keep me around. When we’d finished the table read, we went into the set and began to rehearse with Jay. I was delighted to find that rehearsing the show wasn’t much different from working on a short play. Under Jay’s keen eye, we moved through the set, working with props, finding our best positions, playing the scenes, and discovering the jokes.

Some television shows, especially single-camera shows, are shot out of order; the last scene can be shot first, which makes working in that format similar to working in the movies. Since The Mary Tyler Moore Show was a multi-camera comedy shot before a live audience, going in sequence was customary on show night. Luckily for me, Jay preferred to rehearse the show so the scenes followed chronologically as well, which was in line with my theater training.

I quickly learned the rehearsal schedule. On Mondays we’d meet in the morning and do a full table read of the script so the writers could hear the whole show and make notes to improve it. After lunch, while the writers—who came to be known as “the guys”—were revising, the actors went down to the stage with Jay and started blocking. When we arrived on Tuesday, the writers would hand us blue pages on which they’d rewritten parts of the script. We’d immediately start reblocking the script with the blue pages. Toward the end of the day, the writers would come down from their offices to see how the rewrites were playing. The script was a work in progress at this stage, so we were still on book. I had to learn how to give as full a performance as possible while holding my pages so that the writers and director could hear how the script flowed.

If there were problems, the guys would hole up in their office overnight on Tuesday and hammer out changes that we would receive on bright yellow pages on Wednesday morning. Sometimes we’d get an entire yellow script, not my favorite development but one I learned to work with. Especially because I knew that every set of changes only made the material stronger.

The biggest challenge for me at first was learning how to hit my mark so I’d be in the right position for the camera. In the theater it’s pretty obvious where to stand so that the audience can see you. But I’d rarely worked in front of a camera, let alone three cameras all trained on different angles. Hitting a mark was completely new to me. I had to figure out where to stand so I wouldn’t block Mary or another actor and screw up the shot.

On Wednesday afternoons, the guys would come down to watch the official run-though, which initially made me nervous. I felt under-rehearsed and certain that I’d disappoint. When I told Dick about this fear, he said, “Valerie, you’ve got it wrong. The writers aren’t coming to judge you. They are there to make things better. They are Saint Bernards, coming with brandy to revive you. Help is on the way!” Jim and Allan didn’t mind when I started referring to them as my Saint Bernards.

Thursdays, while Jay and the crew figured out the best angles for filming, the cast would drill our lines with Marge Mullen, our script supervisor. On Fri

day, before set call, the women got their hair and nails done—or, as Mary used to call it, “hairage and nailage.” We’d work through the show scene by scene and then do a final run-through. We’d then break for dinner before the audience arrived, and filming began at about seven P.M.

I loved the pilot script, but you never know how an audience will react. As we were shooting, I heard lots of laughter, so I assumed it went well. Little did I know that it wasn’t the audience we were trying to please but the network brass. The other thing I didn’t learn until much later was that during the initial filming of the pilot episode a lot had gone wrong. The air-conditioning had failed, the sound went out so the audience couldn’t hear, and the network heads were less than thrilled. Jim and Allan knew the show could be much improved and so Grant Tinker arranged for a reshoot several days later. Grant Tinker wasn’t fazed and ordered everyone back to the drawing board.

One of the problems the network had with the show was a character they described as “that awful woman yelling at Mary”—Rhoda! They hated her. Thankfully, Jim, Allan, and Jay were kind enough not to share this information with me, while they set about fixing the problem.

It was Marge Mullen who suggested a way to make my character more likable. Rhoda was very funny but with an edge that was essential. The writers needed to find a way to soften her without sacrificing the comedic big-city brashness.

The initial concept for the show was to have Cloris Leachman’s character, Phyllis, be Mary’s best friend and Rhoda be her foil. Phyllis was supposed to be an elegant, mannered lady looking out for Mary’s best interests. But as Cloris began to inhabit the role, she imbued Phyllis with a studied phoniness that made her amusingly insincere. Marge proposed to the writers that they alter the script so that Phyllis’s young daughter, Bess, be very fond of Rhoda. The fact that a sweet little girl liked Rhoda and her snooty mother did not would signal to the audience that Ms. Morgenstern was definitely okay. I was so lucky they had the talent, willingness, and belief in the character to write these changes rather than to abandon Rhoda and fire me. And kudos to Marge Mullen!

B007Z4RWGY EBOK

B007Z4RWGY EBOK